Introduction

I recently had the opportunity to use Padé approximants. There is a lot of good information available on line on the theory and applications of using Padé approximants, but I had trouble finding a good example explaining just how to calculate the co-efficients.

Basic Background

Hearken back to undergraduate calculus for a moment. For a given function, its Taylor series is the “best” polynomial representations of that function. If the function is being evaluated at 0, the Taylor series representation is also called the Maclaurin series. The error is proportional to the first “left-off” term. Also, the series is only a good estimate in a small radius around the point for which it is calculated (e.g. 0 for a Maclaurin series).

Padé approximants estimate functions as the quotient of two polynomials. Specifically, given a Taylor series expansion of a function ![]() of order

of order ![]() , there are two polynomials,

, there are two polynomials, ![]() of order

of order ![]() and

and ![]() of order

of order ![]() , such that

, such that ![]() , called the Padé approximant of order

, called the Padé approximant of order ![]() , “agrees” with the original function in order

, “agrees” with the original function in order ![]() . You may ask, “but the Taylor series from whence it is derived is also of order

. You may ask, “but the Taylor series from whence it is derived is also of order ![]() ?” And you would be correct. However, the Padé approximant seems to consistently have a wider radius of convergence than its parent Taylor series, and, being a quotient, is composed of lower-degree polynomials. With the normalization that the first term of

?” And you would be correct. However, the Padé approximant seems to consistently have a wider radius of convergence than its parent Taylor series, and, being a quotient, is composed of lower-degree polynomials. With the normalization that the first term of ![]() is always 1, there is a set of linear equations which will generate the unique Padé approximant coefficients. Letting

is always 1, there is a set of linear equations which will generate the unique Padé approximant coefficients. Letting ![]() be the coefficients for the Taylor series, one can solve:

be the coefficients for the Taylor series, one can solve:

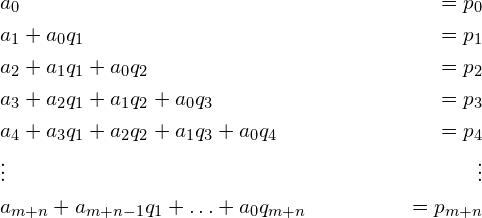

(1)

remembering that all ![]() and

and ![]() are 0.

are 0.

There is a lot of research on the theory of Padé approximants and Padé tables, how they work, their relationship to continued fractions, and why they work so well. For example, the interested reader is directed to Baker (1975), Van Assche (2006), Wikipedia, and MathWorld for more.

Practical Example

The function ![]() will be used as the example. This function has a special representation in almost all computer languages, often called

will be used as the example. This function has a special representation in almost all computer languages, often called log1p(x), as naïve implementation as log(1 + x) will suffer catastrophic floating point errors for ![]() near 0.

near 0.

The Maclaurin series expansion for ![]() is:

is:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[ \sum_{k=1}^\infty -1^{k+1}\frac {x^k}{k} = x - \frac{1}{2}x^2 + \frac{1}{3}x^3 - \frac{1}{4}x^4 + \frac{1}{5}x^5 - \frac{1}{6}x^6\ldots \]](https://www.avrahamadler.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-8d1525a8e97a890b23d8075e96bd97db_l3.png)

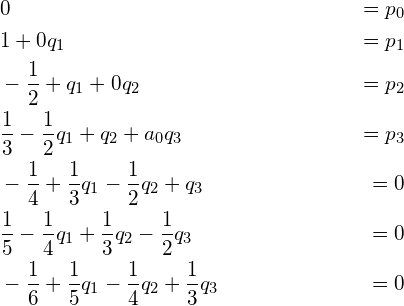

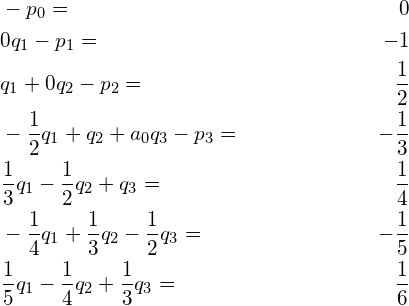

The code below will compare a Padé[3,3] approximant with the 6-term Maclaurin series, which would actually be the Padé[6/0] approximant. First to calculate the coefficients. We know the Maclaurin coefficients, they are ![]() . Therefore, the system of linear equations looks like this:

. Therefore, the system of linear equations looks like this:

(2)

Rewriting in terms of the known ![]() coefficients, we get:

coefficients, we get:

(3)

We can solve this in R using solve:

|

1 2 3 4 |

A <- matrix(c(0, 0, 1, -.5 ,1 / 3 , -.25, .2, 0, 0, 0, 1, -.5, 1 / 3, -.25, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, -.5, 1 / 3, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, -1, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, -1, 0, 0, 0), ncol = 7) B <- c(0, -1, .5, -1/3, .25, -.2, 1/6) P_Coeff <- solve(A, B) print(P_Coeff) |

|

1 |

## [1] 1.5000000 0.6000000 0.0500000 0.0000000 1.0000000 1.0000000 0.1833333 |

Now we can create the estimating functions:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

ML <- function(x){x - .5 * x ^ 2 + x ^ 3 / 3 - .25 * x ^ 4 + .2 * x ^ 5 - x ^ 6 / 6} PD33 <- function(x){ NUMER <- x + x ^ 2 + 0.1833333333333333 * x ^ 3 DENOM <- 1 + 1.5 * x + .6 * x ^ 2 + 0.05 * x ^ 3 return(NUMER / DENOM) } |

Let’s compare the behavior of these functions around 0 with the naïve and sophisticated implementations of

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

library(dplyr) library(ggplot2) library(tidyr) D <- seq(-1e-2, 1e-2, 1e-6) RelErr <- tbl_df(data.frame(X = D, Naive = (log(1 + D) - log1p(D)) / log1p(D), MacL = (ML(D) - log1p(D)) / log1p(D), Pade = (PD33(D) - log1p(D)) / log1p(D))) RelErr2 <- gather(RelErr, Type, Error, -X) RelErr2 %>% group_by(Type) %>% summarize(MeanError = mean(Error, na.rm = TRUE)) %>% knitr::kable(digits = 18) |

| Type | MeanError |

|---|---|

| Naïve | -4.3280e-15 |

| MacL | -2.0417e-14 |

| Pade | -5.2000e-17 |

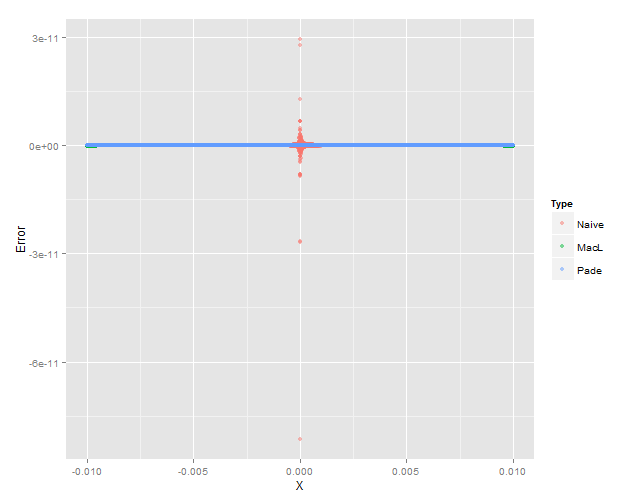

Graphing the relative error in a small area around 0 shows the differing behaviors. First, against the naïve implementation, both estimates do much better.

|

1 |

ggplot(RelErr2, aes(x = X)) + geom_point(aes(y = Error, colour = Type), alpha = 0.5) |

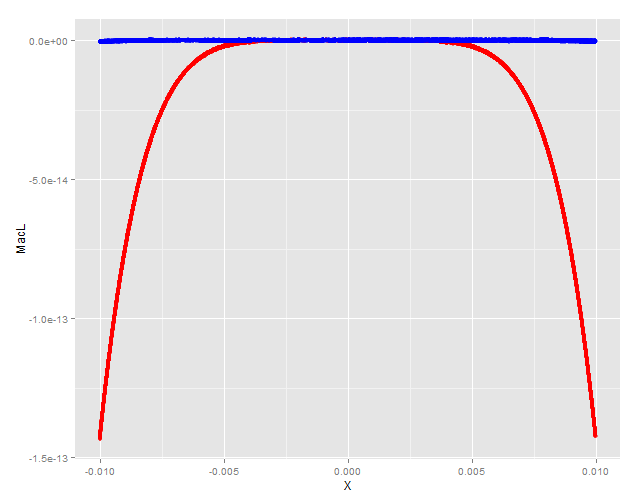

But when compared one against the other, the Pade approximant (blue) shows better behavior than the Maclaurin (red) and it’s relative error stays below EPS for a wider swath.

|

1 |

ggplot(RelErr, aes(x = X)) + geom_point(aes(y = MacL), colour = 'red', alpha = 0.5) + geom_point(aes(y = Pade), colour = 'blue', alpha = 0.5) |

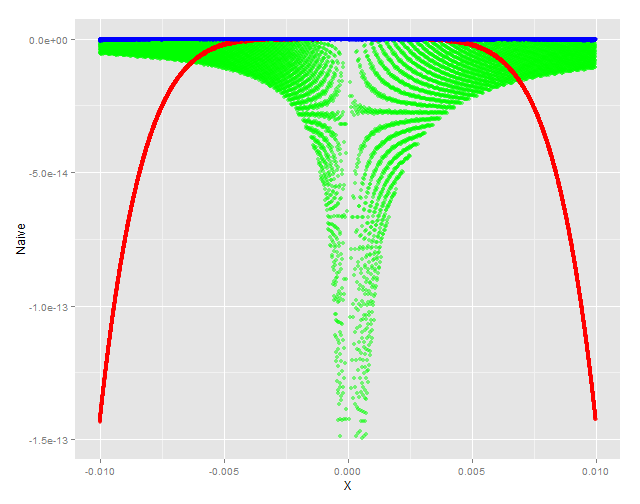

Just for fun, restricting the y axis to that above, overlaying the naïve formulation (green) looks like this:

|

1 |

ggplot(RelErr, aes(x = X)) + geom_point(aes(y = Naive), colour = 'green', alpha = 0.5) + scale_y_continuous(limits = c(-1.5e-13, 0)) + geom_point(aes(y = MacL), colour = 'red', alpha = 0.5) + geom_point(aes(y = Pade), colour = 'blue', alpha = 0.5) |

There are certainly more efficient and elegant ways to calculate Padé approximants, but I found this exercise helpful, and I hope you do as well!

References

- Baker, G. A. Essentials of Padé Approximants Academic Press, 1975

- Van Assche, W. Pade and Hermite-Pade approximation and orthogonality ArXiv Mathematics e-prints, 2006

[…] A Practical Example of Calculating Padé Approximant Coefficients Using R I recently had the opportunity to use Padé approximants. There is a lot of good information available on line on the theory and applications of using Padé approximants, but I had trouble finding a good example explaining just how to calculate the co-efficients. […]